Windows to the Soul

by Olha Samborska

In Ukrainian classes for refugee children, according to the rules of the German Senate of Schooling, there should be twelve children (as the twelve apostles). When I took this position as a teacher of a beginner class, I did not quite understand why twelve. Well, twelve is twelve. “More attention to everyone,” I rejoiced to myself.

But my joy was short-lived. Already in the first months of work at the school, local teachers, whose classes had twice as many children, began to look at me sideways. Some of them smiled sweetly at me, but the coolness was felt in the lower chakras. But I held on. I faltered when the school had a critical situation with the staff and one teacher had to leave the school. Of course, there was fermentation in the masses, because no one wanted to be “superfluous”, that is, laid off.

I once passed a group of teachers on the school playground. “And what is your contract?” I unexpectedly received like a chestnut on the head (we were just standing under this tree). I did not quickly orientate myself and answer, although it is inappropriate to answer such questions as well as inappropriate to ask. My answer caused a goose-cackle among the teachers. I asked what was the matter. They explained about the layoffs, and in their opinion, I “with my three students” should be laid off. In fact, I have not three, but twelve students, but there is a difference for those who have twenty-four or even twenty-eight. The teachers hissed and hollered further, explaining their busy workload. I asked to clarify this issue with the director and left the goose flock.

Soon there was a conversation with the director. The situation was clarified. Teachers of Ukrainian classes in German schools have a special status and are not subject to redundancies that apply to the school as such. I shook my wings, straightened them, and went on my free float around the school. On the advice of the director, I began to avoid geese.

A few more weeks passed. Somehow, after the last week, I understood why there are twelve students in the classes for refugee children, and not twenty-four as in regular classes. When you look at the refugee children, one of whom does not smile at all, the other constantly looks from under his forehead, and you try to pull the soul out of the children to smile and in vain, when you let them out for a break, and after it you can not calm the clots of energy in one wave, when during the lesson you hear out of the blue: “A rocket hit our house and destroyed it,” when the child just heard the word “house” as a trigger. Such “when” surprises are a full lesson and a full day. Gradually, you realise that you are working with children who are really traumatised by the pandemic and war, and in this case this class is equivalent to the class of children with disabilities, who should also be up to twelve, that is, smaller than a regular class, because it is more difficult to work with them. The only difference is that teachers for classes of disabled children are specially trained to work with them. If a disabled child studies in a regular class, a specialist teacher trained to work with disabled children is assigned to him/her and accompanies him/her everywhere.

Of course, Ukrainian refugee children are not disabled in the literal sense of the word, but an individual approach to them would not have been amiss. And the professional qualification of teachers to work with children with traumas would have been useful. And respect for the teacher, who, without special training, has to talk to traumatised children one-on-one, would also not be amiss.

The position of a teacher of the beginner’s class or so called Willkommensclass is new in the German school system. Teachers are usually recruited for it with an emphasis on the qualification of the teacher of German as a foreign language for the integration of the child into the German school. Of course, such German teachers are not always trained trauma therapists. Sometimes one-time and one-hour webinars on how to deal with traumatized children are organized for them. The only thing missing is a systematic methodology for teachers to talk with trauma in children.

Trauma, Ukrainian child trauma, does not speak Ukrainian, as I hoped it would. It speaks to me in the squeaky voice of a child, trapped somewhere between its body and spirit when the war-terrified soul was already on the way to escape from the body, but caught on to the consciousness and hung on to it. It squeaks, sometimes screams, cries, hysterical, as if asking to remove it from the invisible hook of consciousness and pull it out.

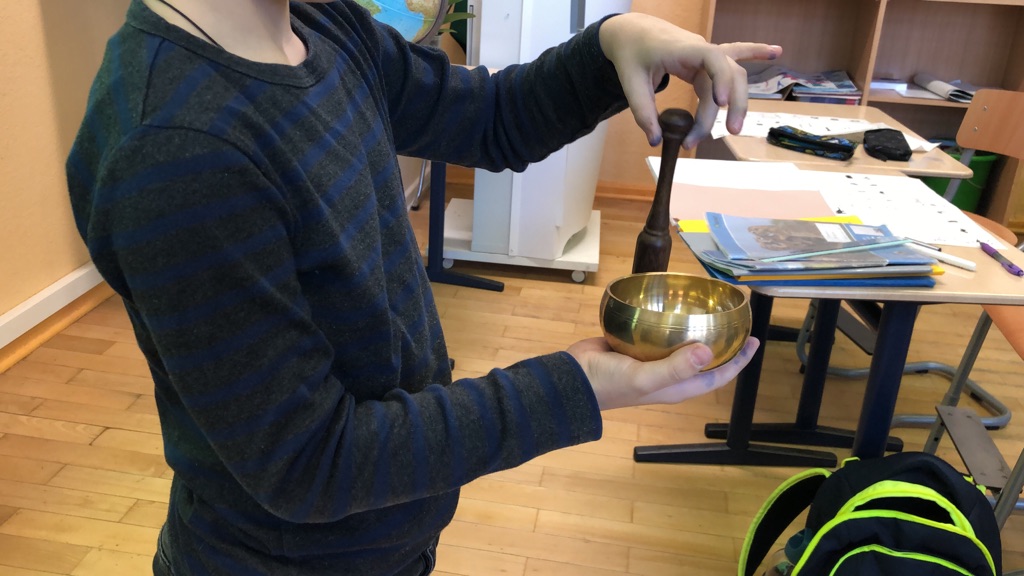

For a long time, I tried to pull out the traumatised soul of the child to talk with, but she was stubbornly silent, only squeaking, bringing the tone of her pain to the maximum volume. Then I decided to listen to the soul in silence. To do this, it occurred to me to use the language of silence and vibration of the Tibetan bowl, which has its own language of sound. I was also inspired by the method of the famous American psychologist, Rick Hanson, and his Di-Po-Za (Breath-Smile-Stop).

The method I used is a direct appeal to the soul, when the child is first asked to focus on himself and his energy with the help of a Tibetan bowl-bell. To begin with, the gong bowl is struck gently. The delicate sound resonates with the trapped soul. Then I ask children to take a deep breath to get even closer to the soul. When the child exhales deeply, the space in the body (lungs, heart, inner cavity) is freed up, where the soul can take its original position again. Once before the war, before the shock, it was here, taking its rightful position, breathing on a free chest, smiling.

I ask the child to smile inside himself. It is enough to fold the lips into a smile. This will help the soul to remember how it used to smile. It is desirable that the child stay in this state and give enough time to the soul to remember the smiling state. This step is called Stop or Holding, the last of the three steps of Di-Po-Za (breathing-smiling-stop). The end of this smiling conversation with the soul of the traumatised child is marked by the gong of the bowl so that the soul does not escape and remains in the body. In this way, the child seems to return to himself and then you can conduct a full lesson.

It is important that the child loves the bowl and its sound. For this purpose, for some time before using the method, I introduced the children to the bowl. The bowl is freely available in the classroom. Pupils could take it in their hands, “play on it,” and practice their abilities as a small meditator. I chose the smallest version of the bowl so that it fits in the palm of a child’s hand. When the bowl fits in the palm of the hand (as if God or nature made a hollow in the palm of the hand to hold the bowl), the child gently strikes the side of the bowl with his free hand. Metal vibrations pass through the nerve endings of the hand, reaching the scratched soul on the very edge. These vibrations seem to collect or rewire the neural connections damaged by trauma, reading their original print from a common server somewhere in the heavens. The traumatized brain puts the pieces of neural synapses back together. Children intuitively feel the therapeutic effect of the bowl, because they often ask to hold it or “play” on it. Of course, everyone is given such an opportunity.

Not all my students smile sincerely yet, but the frozen windows of their souls are gradually thawing. If you regularly practice Di-Po-Za, smile at the traumatized child’s soul, you can thaw the windows of their souls, through which you can better see the child, and maybe the apostle in it. One of the twelve, or perhaps all of them.